Jay Gatsby vs. The American Dream

11 min. read

An Introduction

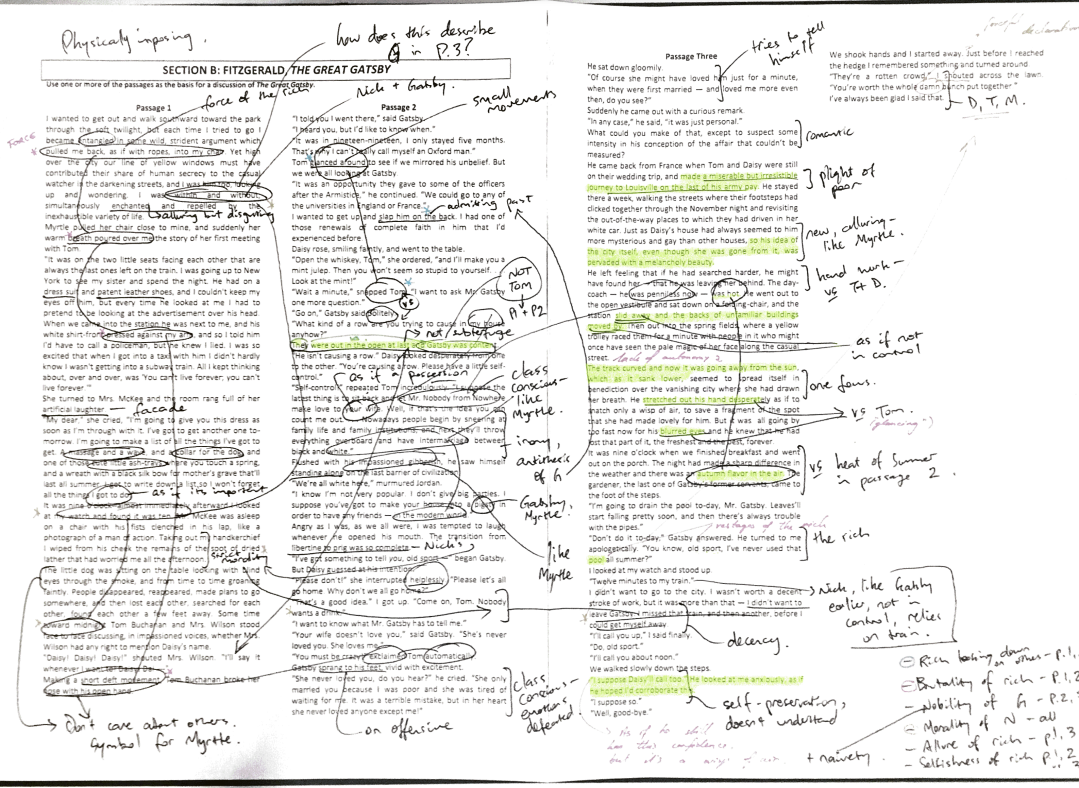

Through Gatsby becoming cognisant of losing 'that part of it, the freshest and the best', Fitzgerald presents the illusive wealth and prosperity with which he is eventually faced. In seeing his dreams permanently dissipate into fiction, Gatsby's struggle becomes representative of the ultimate result of such an era as the roaring Twenties, where 'high over the city', the wealthy push away anyone who offers a perceived threat to their security and old money status. Gatsby, like Myrtle, is offered to the reader as a victim of this divisive society, yet to Fitzgerald, the real tragedy lies in how those who suffer at the hands of this capitalistic environment are both 'within and without', constantly propagating the ideals of the very system which so ruined them.

Women of New York

The intrinsic confidence in Tom 'glanc[ing] around' becomes representative of Fitzgerald's wider portrayal of the security and power bestowed upon the men of this rich elite. So assured is he of his authority in passage two that he can adopt such an aloof stance even in this rather tense environment. Though Tom wanting to reassure himself that the others 'mirrored his unbelief' may well allude to a latent fragility in his demeanour, that he should do so with such nonchalance and indirectness reaffirms his sense of superiority. Daisy, on the other hand, can only be described throughout the passage as smiling 'faintly' and interrupting 'helplessly'. The use of the adverbial construction here augments the contrasting mannerisms of the Buchanans; so fundamentally destitute is Daisy in this passage that her very attempts at such pleasantries as humour and mediation become associated with her fragility. Tom, conversely, 'snap[s]' at people, with the harsh and spontaneous connotations of such a tone confirming his own perceived righteousness. To the reader, then, what Fitzgerald presents is a blatant asymmetry in the dynamic of the relationship; Tom, on account of his overbearing masculinity, possesses legitimate leverage whilst Daisy merely looks on 'desperately'. Indeed, this dialogue offers an insight into the general influence men have on the goings on around them. Likewise in passage one, even when Tom is 'look[ing] at her', Myrtle cannot reciprocate this eye contact. Such a double standard is only furthered by Myrtle feeling she 'had to' do so, generating the impression that this dynamic is one she is compelled to oblige to. Given the differences in class of the two, that Myrtle later 'didn't hardly know [she] wasn't getting into a subway train', this interaction becomes representative for Fitzgerald of the prevalent status of men in this capitalistic society. To Myrtle, her experience of Tom is presented as being a dream of sorts, as if meeting a man of his exuberant wealth is, for a woman of her background, an utter improbability. Not only was she, just like Daisy in passage two, unable to be nowhere near as affront as Tom is, but at the same time, 'all [she] kept thinking about' was how fortunate she was to be in such a position. In essence then, Fitzgerald critiques this era where women of all classes are not only totally subservient to these wealthy men, but ultimately idolising of them too.

Dirty Money

More than just representing an underlying inequality across relationships in the upper societies, Fitzgerald pities the ultimate abuse which aspiring outsiders of the time were exposed to and how decisively they are at the mercy of the rich above them. Such corruption is manifest between Tom and Myrtle, where, in passage one, with 'a short deft movement' he breaks her nose. Here, the blunt, monosyllabic description functions to reaffirm the inhumane treatment inherent to such a deed, establishing the indomitable force Tom is capable of wielding against those he sees as threats to his security. Indeed, for Fitzgerald, this 'open hand' with all its sweeping brutality, epitomises the cruelty innate to this social elite. Rather than engaging in democratic conventions, Tom, a beneficiary of the authority inherent to his class and sex, actively silences what he perceives as dissenting voices. Moreover, that this should be about Myrtle having the 'right to mention Daisy's name', renders Tom's dismissal all the more jarring. Though American women had just received suffrage at the time of the novel, Fitzgerald still seeks to unmask in this capitalistic society what he sees as illusory equality. Though Myrtle may think she can 'say Daisy's name whenever [she] want[s] to', this appearance of authority is ultimately for the readership extinguished by the blunt hand of masculine judiciary. Gatsby, too, similarly aiming to escape the lower classes, is as subject in passage three to the castigating currents of the upper elite as Myrtle is. Having come to Louisville 'on the last of his pay' Fitzgerald presents Gatsby to the reader as having sacrificed all pecuniary security in the hopes of realising his ambitious dream. Yet, rather than leaving satisfied, he is left 'snatch[ing] only a wisp of air'. The utter insubstantiality of such imagery, indeed the sheer impossibility of catching a hold of nothing, suggest the ultimate hopelessness of Gatsby's experience in this world, one which promotes dreamers like him, but delivers only the most insignificant and ethereal sensation of the happiness it promises. To the reader then, Fitzgerald holds people like Gatsby and Myrtle up as victims of the pervasive inhumanity of the Roaring Twenties, people who in the end could only passively watch as 'the station slid away and the backs of unfamiliar buildings moved by'. Fitzgerald denounces not only how these people are left void of all the joys and prosperity assured in the American Dream, but how they are stripped of their autonomy in the process.

A Fantastical Addiction

Despite these dire prospects, however, this lifestyle of materialism is one that Fitzgerald laments as attracting each and every one of his characters, regardless of what it may make of them. Such a dependency is characterised through Gatsby making his 'miserable but irresistible trip' back to find Daisy. Through such an oxymoronic construction, Fitzgerald makes clear the underlying addiction Gatsby has to his dream, that regardless of being conscious of the solemn path which lies ahead, he is swept up anyway - this society, for all its insubstantiality, still simultaneously enchants. Nick is likewise prone in passage one to the seductive currents of the wealthy elite, becoming constantly 'entangled' by a party of people from which he actively 'wanted to get out'. Nick, here, cannot even specifically determine what it is that so ensnares him, it is merely 'some wild, strident argument' which spins out its inescapable web for him. Through such general, ambiguous descriptions, Fitzgerald portrays the troubling elemental tides that so allure us to the glamour of this society; whereas Gatsby in passage three had a definitive vision in mind on his trip, Nick, even though he cannot conclude why exactly he remains, is nonetheless 'pulled…back, as if with ropes'. To the reader, then, he merely becomes some passive vessel at the hands of the temporal aristocracy he finds himself with. Though he may be 'repelled' by their 'variety of life', he is still 'enchanted' with this gaudy abundance. Whilst there does exist throughout the text such open manipulation of power from the likes of Tom and his old money associates, Fitzgerald ultimately decries the materialistic structures which can inspire so many suitors like Nick and Gatsby even after they become aware of just how insubstantial it all is. Most disheartening to the readership, then, is how even after the dreams of men like Gatsby are so clearly over, their view of reality has become 'pervaded with a melancholy beauty', depicting just how far reaching the damage is. For all this society has taken from them, their eyes have become, for Fitzgerald, largely blinded by the very glimmer of the gold after which they so desperately chase.