Marlow, Kurtz and The Congo Redemption

13 min. read

An Introduction

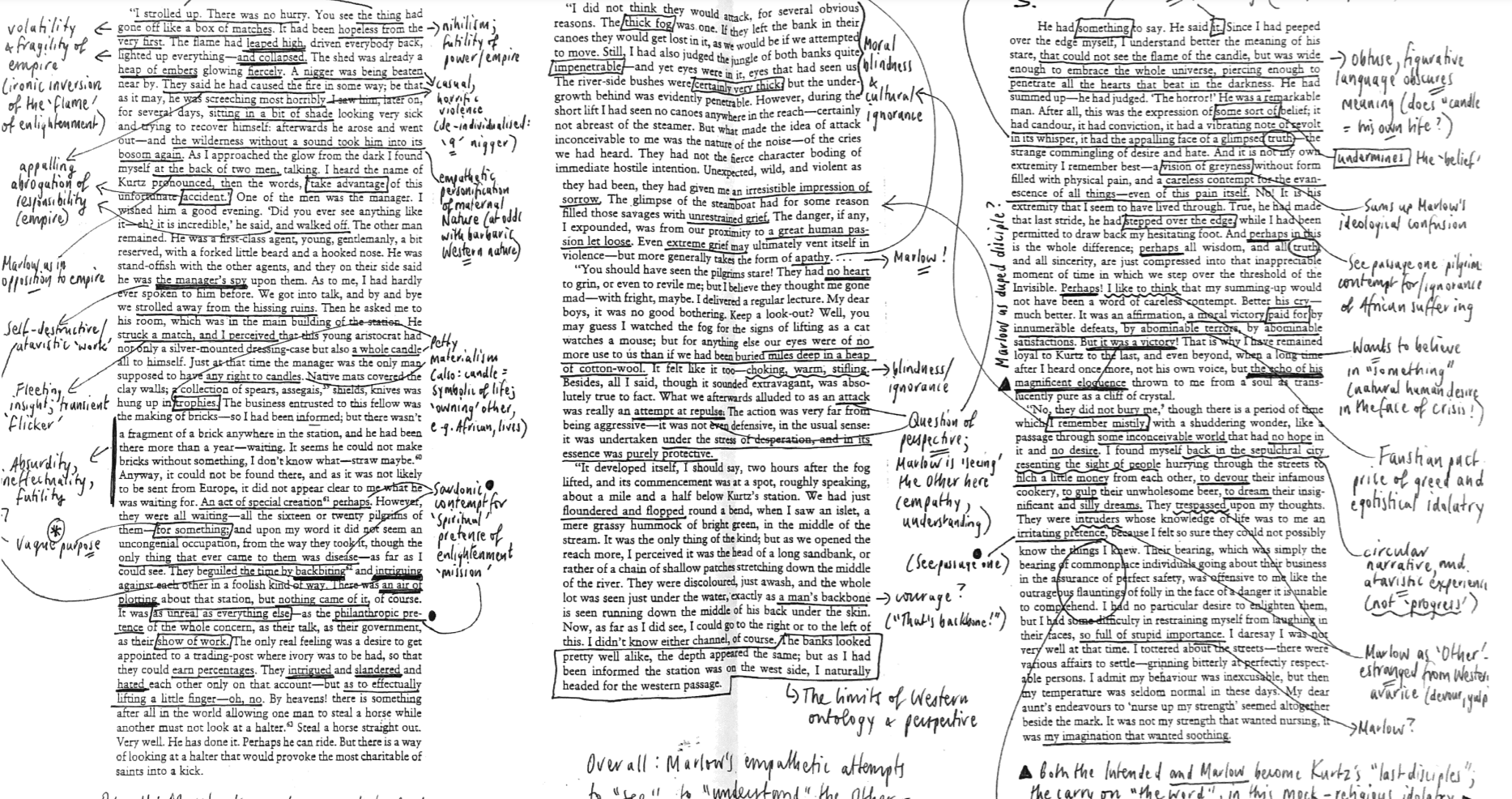

As Marlow emphatically declares the “moral victory” of Kurtz’s existence and the “wisdom” and “truth” interlaced in his work, his words recreate the lexicon of late-19th century Western rationalism, one that insistently sought to sustain its own projection towards some fixed point of ideological certainty. Yet Marlow’s own convictions are far from resolute, as is evident in his own vacillation between a detachment from the hollow and ineffectual “air of pretence” and an emergent comprehension of a universal humanity between himself and the African subjects, seen through the “eyes” of the jungle that seem to reach out and collapse the physical chasm between the ‘boat’ of colonial certitude and the previously “impenetrable” jungle. So, as the “choking, warm, stifling” fog sets over passage two, Conrad figuratively evokes the upending of Western ‘vision’ and its inherent determination to hold true on imperial claims of learned truths and enlightenment.

Impending Apathy

The lethargic rhythm and droll melancholy of passage one’s opening – “I strolled up. There was no hurry” – evinces a note of cursory indifference in Marlow, one that foreshadows his growing disillusionment with the rapacious underbelly of the late-Victorian colonial enterprise. Set against an intervention crafted by a redeeming vision of enlightenment, this “torch” of moral authority is subverted, itself becoming the “flame” that enacts destruction, rather than cultural growth. In Marlow’s eyes, he finds himself antagonised from the supposedly civil imperatives of colonialism, principles that, as seen in this passage, rapidly descend into the perfunctory horror of “A nigger…being beaten nearby”. The staccato, blunt fricatives work here to jar against and cut through the lingering ideals of empire, creating a bitingly crude aural quality that both reinforces Marlow’s apathy towards the colonising experience as well as the brutal and atavistic core of this expansion. This darker subtext of immorality is one that does not allow itself to be openly paraded beyond Marlow’s retelling, unlike the “native mats”, “shields”, “knives” and “trophies” that hang ostentatiously in the agent’s room, rendering the display a turgid shrine to the glories of European intervention. However, such relics latently attest to the way in which the West takes hold of ‘the Other’, deforming the African subject and its culture into something to be itemised and collected, or else savagely beaten for its alleged misdemeanours. This squares in many ways with the ‘grand narrative’ of empire – the pilgrims in possession of the ‘native’, yet the sibilant “hissing” of the flames and the “screeching” that painfully grates for readers erodes any lasting “philanthropic pretence” as to the morally redemptive heart of the supposed ‘mission civilisatrice’. Instead, it is an enterprise that inflicts suffering and shackles, rather than liberates, the colonised. So, as Marlow approaches “the back of two men”, Conrad offers an image that captures physically what his sardonic voice insists on syntactically throughout the passage. Like the ship “firing into the continent” aimlessly that greets Marlow on his arrival in Africa, this station resorts to a state of “backbiting”, “intriguing” and “plotting”, plagued by a decided lack of progress, a form of stagnancy, as the present continuous verbs suggest. As such, in the first passage Marlow appears to distance himself from the attendant sense of chaos and destruction that is embroiled within the place, a form of hegemony decidedly absent from the frame narrator’s earlier eulogising panegyric to the West, and to empire more generally, as a morally righteous entity.

Marlow and Voice

However, Marlow’s voice passively isolates him from empire, and his empathy for the “extreme grief” of the Congolese strikes a chord of emotional connection between them, suggesting a commonality that dismantles the West’s ‘Othering’ of the African landscape and its people. Whilst there are aspects of Marlow’s narration that play into these traditional binary depictions of coloniser and colonised – the lingering note of “they” being a foreign and therefore threatening “savage” – he becomes increasingly cognisant of the alluring and “irresistible impression” of the nature and the subject bound within it, as the sibilance tacitly augments the beguiling aspect of it, especially in contrast to the blunt beating given out in passage one. Indeed, set against the defunct and decaying station of the first passage, this passage runs the gamut of the unbounded extremes of emotion – an “unrestrained”, “wild”, “violent” “sorrow” – a lexicon which procures both the lively humanity at play here as well as the potential for such emotions to evade suffocation by a Western insistence on rationalism, on rendering the equivocal definitive. Marlow’s tone here waxes poetically in his ruminations on this “great passion let loose”, as he gesture towards that which is “human” and therefore beyond the Manichean dichotomies of the European and African subject that shape Western rhetoric. Contrary to the purported infinite reaches of the West – be it in the imperial maxim “The sun will never set on the British empire” or the projection of Europe as the “beginning of an interminable waterway” – there are , the author implies, limits to this vision of the world, a vision that fittingly becomes, in this passage, “buried miles deep in a pile of wool”, as Conrad offers an image of its own potential blindness to the ambiguities of the human experience that subvert the imperial enterprise and its assumptions of ideological absolutism. Indeed, where the West’s invasion atrophies both its own endeavours and the African subject, the jungle, a recurring motif for the author of human nature, takes the wounded “without a sound…into its bosom again”, with the graceful aural palette of this statement pairing with the image of a fecund Mother Nature to impose a message of nurturing benevolence, rather than destruction. Ultimately, therefore, as Marlow sees himself becoming all the more disenfranchised with the sordid reality of his pilgrim mission, he simultaneously works to penetrate through the muddy waters of his ideological disillusionment and thus map out for his listeners on board The Nellie the potential of a universal humanity.

Kurtz As Redemptive

Paradoxically, however, even Marlow finds himself in the shroud of his own ‘fog’ of delusion, as he yearnfully holds on to the “moral victory” of Kurtz’s work as means of rectifying his own ideological despair in the face of his conflicting experience. The further he drifts away from the fortitude and certainty contained within Western rhetoric across the passages, the more pronounced his tonal shift becomes, transitioning from patronising mockery – “but as to effectually lifting a finger – oh, no.” – to a wistful optimism and then finally here to desperately proclaiming the definitive way in which Kurtz “had summed up” and “judged”. His zealously idyllic portrayal of Kurtz having some sort of “conviction” is echoed in the pervasive deployment of the perfect past construction “had”, which, in conjunction with his perfunctory summations that dominate the opening paragraphs of passage three, communicates Marlow’s desire for something left untouched and unpolluted by the otherwise grotesque ‘present’ of empire which he occupies. Of course, how this “glimpsed truth” manifests itself, the reason “why” Marlow so fervently proclaims his loyalty to Kurtz, is left purposefully cloaked by the pall of his syntactical imprecision. In doing so, Conrad not only defies literary convention, which insists, more commonly, on a final and lasting sense of closure, he also augments the ominous quality captured in the “vibrating” fricatives of this “revolt”. In seemingly worshipping the ‘voice’ of Kurtz, even the hollow and insubstantial “echo of magnificent eloquence” that remains, Marlow becomes a tragic “last disciple” of Kurtz, an adherent follower of ‘the Word’ of this quasi-spiritual figure, however morally dubious his doctrine was. This is understandable in some sense, given the “vision of greyness” which has settled over his psyche, an impending “careless contempt” that offers neither the supposedly pure enlightenment of imperial rhetoric nor the absolute ‘blackness’ of having “stepped over the edge”. It is this enervating nihilism that leaves him to “totter” about the streets upon his return, needing to “nurse up [his] strength”, and through this image Conrad suggests that colonialism is destructive on two levels: not only does it orchestrate the physical violence implied throughout the first passage, it also wears down on the psychological space of those who participate in it. Instead of arriving at some panacea of certitude or ‘cracked-nut’ truth that could resolve his fractured certitude, Marlow appears to earnestly convince himself of the capacity for Kurtz to vindicate the “evanescence of all things” that looms over him. As such, this extract becomes one of the darkest in the test, ironically, given how dutifully Marlow proclaims to see the ‘light’ of Kurtz’s vision of humanity, the stare “wide enough to embrace the whole universe”. Yet in such absolute vernacular, his insistence on Kurtz capturing “all wisdom” and “all truth”, Marlow actively glosses over the inherent complexities that Conrad communicates, subtextually, to his late-Victorian readership. Even as Marlow recounts his journey up the river in a form of retrospective reflection and mental catharsis, by the final pages of the novella, he is still prepared to uphold Kurtz as a redemptive beacon for the otherwise impenetrable ‘fog’ of the colonial enterprise, something he can “bow down before and offer a sacrifice to…”.

On The Pall of Western Rhetoric and Colonialism

More coming soon...