On The Pall of Western Rhetoric and Colonialism

15 min. read

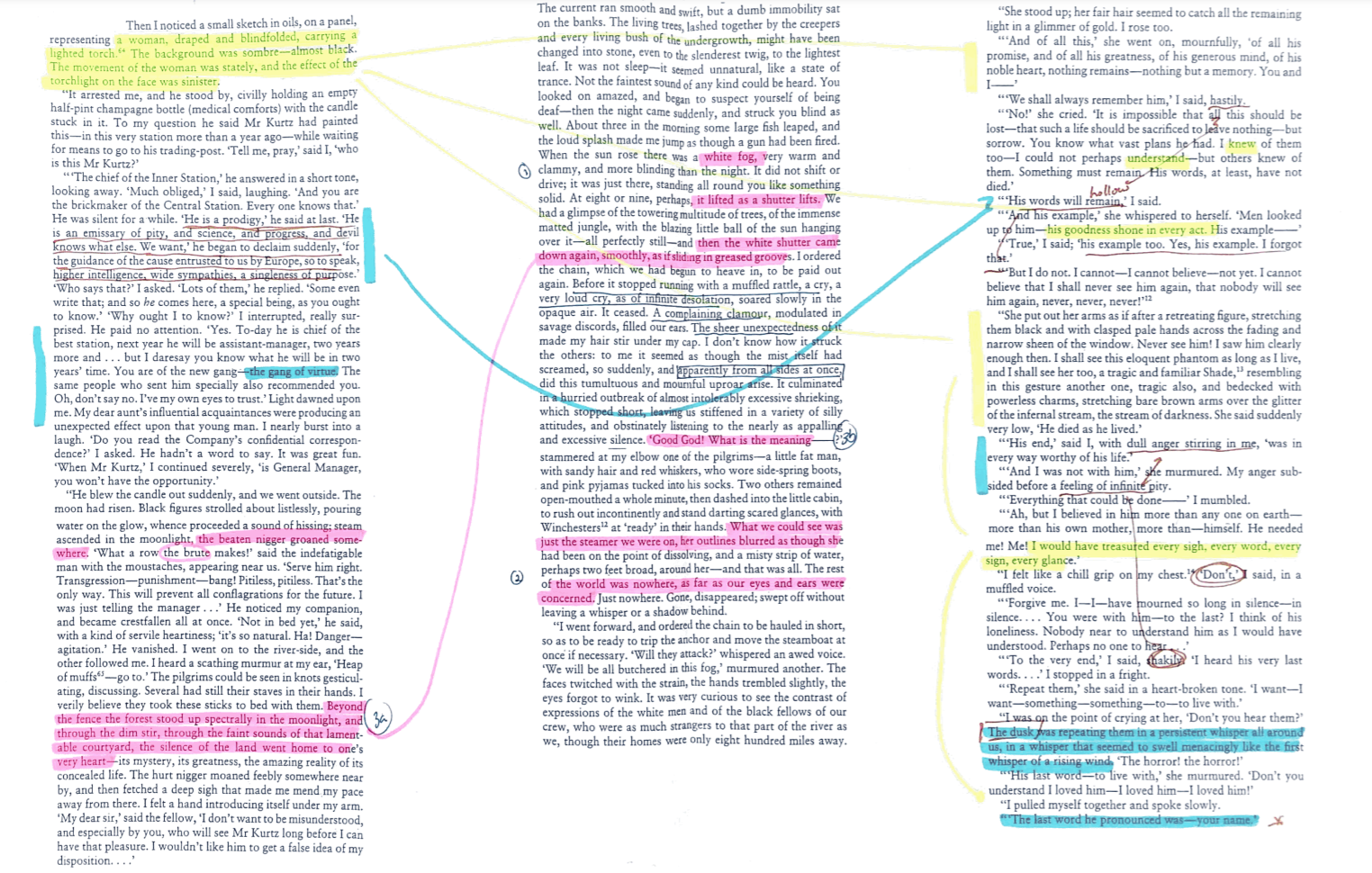

An Introduction

The “intolerably excessive shrieking” in the second passage – in its evocation of something irrationally “appalling” and jarring to the West’s comprehension and sensibilities – reveals the limits of understanding, the potential for this raw, untapped emotion to elude Western reliance on rationalism as a means of interpreting humanity. In the figure of Kurtz, his portrayal as a “prodigy…of science, and progress” epitomises the moral hypocrisy at the core of colonialism, its insistence on carrying forth the ‘torch’ of its learned wisdoms to map out the “darkness” of the African continent. So, in this rapacious underbelly masked by the ornate rhetoric of empire, Conrad prefaces the difficulties of moving past what “remains” of these institutions and interrogating these systems in a thoroughly sceptical and modern fashion.

The Fog of Colonisation

The nebulous “white fog” of passage two that descends upon the river at sunrise conveys how nature, in Conrad’s eyes, can impose a decisively opaque film over the colonising experience. This “warm and clammy” mist of an uncomfortably sweltering, if not suffocating, Congolese jungle paradoxically becomes thicker even as the “blazing little ball of the sun” rises, contradicting such a motif’s immediate association with enlightenment and learned comprehension, as it can only “hang” above the landscape, powerless to thwart the tenebrous submersion into a place “more blinding than night”. Set against this fragility, the reader is presented with a depiction of nature engendered with an exotic allure, as Marlow’s voice appears to wax poetically, and at times mournfully, in his descriptions of the African wilderness – “through the dim stir”, “through the faint sounds of that lamentable courtyard”. The rhythmic impress at work here evokes a quality of replenishing vitality, one that exists “beyond the fence” of the colonialist station, able to penetrate across to the reader “through” the otherwise wilting and decaying pilgrimage before it, be it the figures “strolling about listlessly” or the “hurt nigger” that moans “feebly” in Marlow’s vicinity. This resonating captivity contrasts with the jarring and brusque “little fat man” that emerges in the second passage, whose bewildered cry of “What is the meaning---?” is suggestive of a Western insistence on forcing an unequivocal form of rationalism onto the pulsating entity of the jungle, a seemingly vain attempt, given the way Conrad works to sustain this landscape as defying ontological transparency in these passages. Indeed, the language of the unbounded that Conrad weaves into the “complaining clamour”, that rends the sinister tranquillity imposed by the “white shutter”, speaks to a forlorn and distinctly human anguish that appears to have “soared” beyond the comprehensible, an “infinite desolation” within which an unquantifiable, and therefore incommunicable, sorrow is embroiled. These pilgrims aboard the steamer present themselves to the reader, in this instance, as confounded by the “sheer unexpectedness” of this melancholic howl, left disconcerted by a “cry” that seems to defy common sense and reason as it comes at them “from all sides”. Writing for a readership that no doubt still subscribed to the notion of sight or human vision as gesturing towards a form of objective reality, Conrad clearly works to suggest otherwise, that perhaps the European persistence of upholding logic and rhetoric falls short of something more in the human experience, a more emotional and longing cry of pain. As in this passage, it is the reverberating sounds that defy any sort of translucent meaning – in their suggestion of human agony – that “filled” the ears of the colonisers; their vision however, can observe only a “blurred” world that seems to go “nowhere”. In this way, the complex and inscrutable quality of the African jungle, from which the harrowingly humane voice of suffering emanates, attests to the shortcomings of Western sensibilities: a desire to reduce the muddied “fog” of nature – and thus by extension human nature – to an unequivocal and rational vision of things, but a desire for grand narratives and rationality that belies the inherent pains and ambiguities of humanity.

Western Justice and Morality

And so, in the face of such destabilising threats to Western ontological convictions, the “woman…blindfolded” in passage one serves as an insidious image of a willingness to obfuscate this more sordid reality. In an effort to uphold the systems of late-19th century empire, there is a troubling sense of the figure’s enthusiasm in her lack of sight, as she is depicted as “carrying the lighted torch”, actively participating in bringing forth the symbolic enlightenment of European colonialism. In many ways, this moment of wilful dissemination of the ‘Enlightenment’ of Western thought is fitting, given how the sketch is a latent evocation of the goddess of justice Astraea, as Conrad maintains a message of a corruptive, rather than nurturing, civilized morality inherent to this form of imperialism. The reader, over the course of passages one to three, becomes aware of the purposeful parallels Conrad draws here, as the Intended’s “fair hair” - set against her despondent, if not at times naively hopeful tone – echoes the “stately” yet “sombre” quality of the painting. The lexicon of ideological optimism that pervades this passage – the repeated desire to “understand” and “know” what her husband intended – gestures towards an unequivocal belief in the potential for logical triumph, the potential for unambiguous knowledge by which she can progress forward. Her efforts, however, are undermined, rendered vain, as she can only speculate on how she “would have treasured” Kurtz’s every action. There is a clear subtext of idolatry, here, as her insistence on her now deceased betrothed as some immeasurably valuable figure upholds him as a dubious deity, someone to be “believed in…more than any one on earth”. This sentiment is captured in her being likened to a “tragic and familiar Shade”, protecting Kurtz on his figurative journey to Elysium and thereby engaging in a form of apotheosis, transforming him into an insidious and grotesque form of god. Yet the fragile longing of her outstretched arm and “powerless charms” renders this symbol of worship hollow, as the Intended is left to stretch her “pale”, lifeless hands “as if after a retreating figure”, reaching out for something definitively insubstantial and ephemeral. Given the spectral female role throughout the novella, this image could, on one level, be read as Conrad’s patronising tendency to place women outside of the confronting and opaque locus of imperialism, implying that they are too sensitive to fully comprehend the moral bankruptcy of empire and the enervating mist of the African jungle. Yet more universally, this passage portends the hollow veneration of, and deceptive rhetoric “draped” protectively around, colonisers like Kurtz, whose redeeming “goodness” in life can only result, for Conrad, in the idea of European colonialism being rendered at once transient and vacuous, despite attempts to extend it into perpetuity and thereby providing, however dubiously, a comforting ideological system “to live with”.

The Spiritual Wasteland

Yet even with this more fragile and tenebrous reality that befalls the Intended, Marlow’s largely patronising inflection in this passage initially rings with a disgust for her fugacious veneration of Kurtz. She is, in this moment, quite clearly distraught, as the “mournful” quality of her voice, in conjunction with her at times fragmented and incoherent speech, speaks to a lamentable sadness to her aspect, a wistfulness with which Conrad asks us to sympathise. In contrast to such melancholy, the way Marlow “hastily” drives forth the conversation and his almost comically echoing remarks – “His words will remain”, “his example too. Yes, his example” – conveys a sardonic tone that seems to generate the impression of his detached antagonism to the Intended’s emotionally-fraught yet desperate admiration of Kurtz. The hollow rhythm of ennui in his voice, on one level, seems to allow Marlow to distance himself from such ruminations on this now-dead figure, a veneration that has been rendered vacuous and myopic in light of the harrowing journey of epiphanic enlightenment he has endured regarding the dark opacity of human experiences and man’s capacity for corruptive hegemony. Perhaps on a deeper level, too, he appears insistent on maintaining a pretence of moral objectivity and thus can remain beyond the supposedly irrational and fragile world of human emotion in which Kurtz’s betrothed finds herself. Yet, Conrad works to disrupt Marlow’s pretence of a cohesive civility with the passage’s development, as the author communicates a subtext of parallels between Marlow’s own veneration of Kurtz and that of the Intended. The “chill grip” that latches onto him as her blind adoration comes to the fore stands as a cold, morbid image of the impending realisation that seems to dawn on him here: having already held up Kurtz as a potential redeeming figure of European colonialism, Marlow no doubt sees his own visionless ontological subscription to the rhetoric of empire in the Intended’s anguish here, as the tonal transition in his voice from condemning certitude to “shakily” extending a “Don’t” by way of interjection crafts an underlying note of hesitancy in the passage, and Conrad erodes, therefore, any notions of a pompous disposition. So, in this moment, not only does Marlow begin to comprehend the naivety of his formerly romanticised and bombastic visions of Western empire as potentially redeemable but as a consequence, Conrad’s perception of the fundamentally cyclical nature of so-called human progression comes to the fore. Counter to liberal humanist assumptions asserting an inexorable European ascension towards a set of objective moral ideals, and despite Marlow having travelled up river into the depths of his own ‘darkness’, the novella presents, in the Intended a troubling conclusion of epistemological stagnancy, one that Marlow himself ensures by ‘sacrificing’ the truth and doing the one thing he finds “detestable”: lying, in this case, about Kurtz’s “last word”. And so, just as the text opens with a “haze” that settles over the Nellie “at rest”, in this moment with the Intended, Conrad affirms both the circular path of colonialism’s deception as well as the psychological challenges closed within the “black bank of clouds” that lead into “the heart of an immense darkness”.

Marlow's Internal Journey, Through the West, Towards Kurtz

Marlow, Kurtz and The Congo Redemption