Marlow's Internal Journey, Through the West, Towards Kurtz

21 min. read

An Introduction

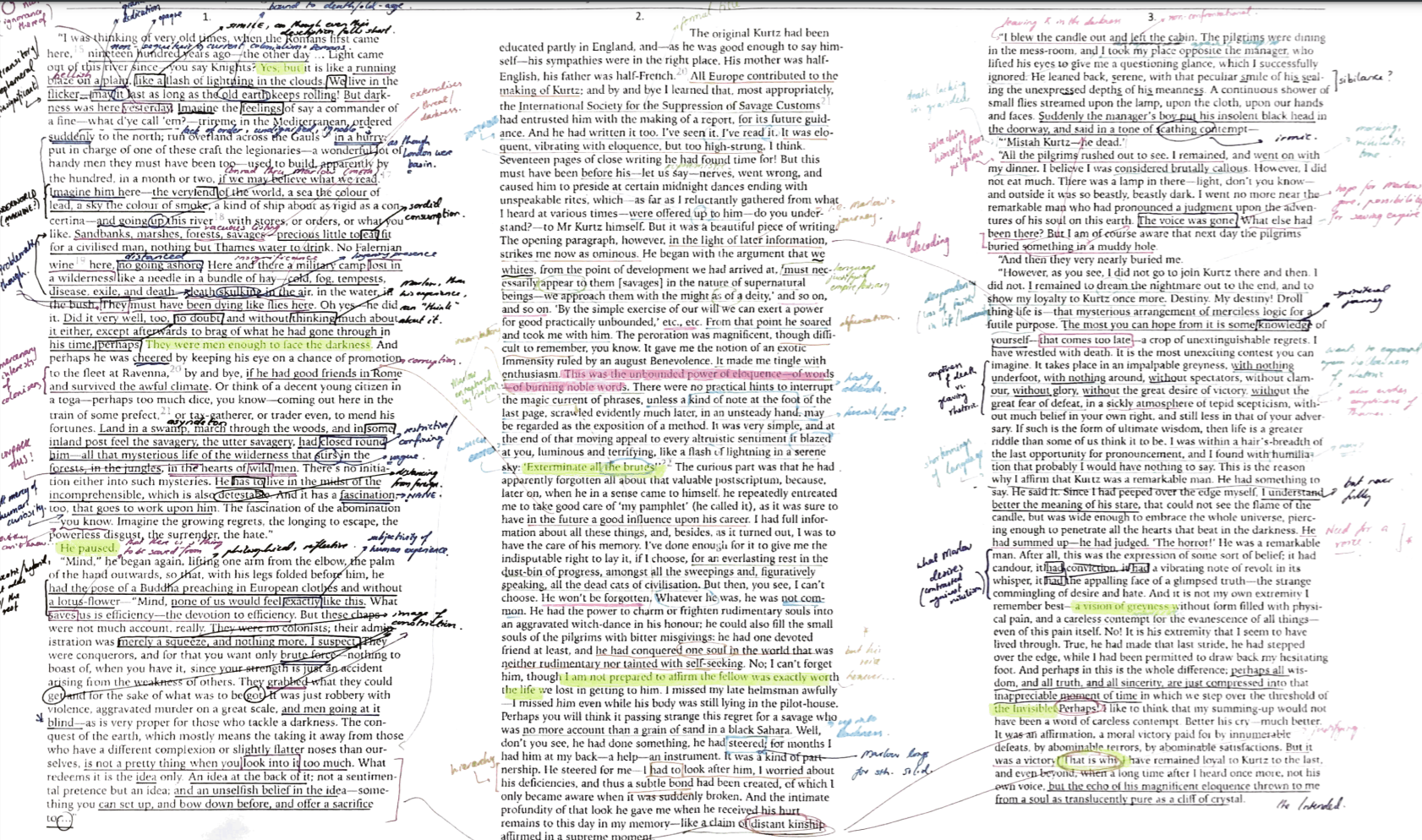

The relentless and insistent nature of the asyndeton in passage one – “the growing regrets, the longing to escape, the powerless disgust, the hate” - synthesizes a tone of veracity in Marlow’s voice as he depicts an ominous colonising experience at odds with the “unbounded power” for civilising measures promised in the writings of Kurtz. This is, for Conrad, symptomatic of his pre-modern Europe, where the morally corruptive constructs of empire were glossed over in “magnificent” peroration that had, perhaps, thrilled his bourgeois readers in the decades prior, captivating them to “tingle with enthusiasm” at the alleged redeeming capabilities of Western imperialism. Writing at a time of emerging loss in faith of colonial structures had begun to emerge, Conrad aims to relate the traumatic cognitive redress of such a transition away from a belief system that had, up until the late 19th century, formed the backbone of the West’s economic and cultural stability. It is this “humiliation” of coming to terms with the notion of unscrupulous European hegemony, paired with the “impalpable greyness” that Marlow speaks of in passage three, that depict his emotionally bereft condition, as he comes to terms with the moral failings of empire in the absence of any reassuring articulation from Kurtz. Yet in Marlow’s attempts to retrospectively reconstruct to himself what this figure represented – “he had summed up – he had judged” and thereby salvaging his faith in the man and what he may have represented, Conrad begins to implicate an innate need for absolute meaning, especially in the absence of the epistemological foundation of colonialism.

A Crumbling Empire

Contrary to late-Victorian assumptions of an eternal Western civilisation, “the flicker” Marlow speaks of in passage one denies his – and Conrad’s - conservative readership of any such comforting longevity in its colonising endeavours. The “lightning” and “running blaze of the plain” may seem to evoke, on one level, the traditional glorification of Western empire in their insistence on an altogether grand and natural entity. Yet, these phenomena themselves are, like the short-lived fire of imperialism, fleeting - a “flash” that, whilst capable of great damage in the sinister “clouds” of an ominous immorality, is rendered paradoxically ephemeral. Indeed, that European expansion into a purportedly ‘uncivilised’ African realm is only “like” such grand forces augments its transitory quality; a Western institution that is not only distinctly temporary, but fails to deliver on even the immensity of this “sacred flame”. Marlow’s latently sardonic tone in this passage’s opening - “may it last as long as the old earth keeps rolling” - foregrounds Conrad’s challenge to liberal humanist assumptions of an immutable societal progression, an inexorable ascension grounded in the “light” of civil refinement that coming out of the “river” of Western thought since the romanticised era of the “Knights”. Ironic, however, is that this “venerable stream” of supposedly enlightened ontology was itself once the outpost of Roman colonialism, situated at the “very end of the world” as a barbarous and hellish site of “cold, fog, tempests, disease, exile and death”. In characterising London as an abominable landscape at the margins of this historical society, far removed from the heart of this ancient European empire, Conrad decentralises the town and thus removes any reaffirming notion for his readership of Western cynosure. Moreover, the ubiquity of temporal qualifiers throughout this description – “nineteen hundred years ago – the other day”, “darkness was here yesterday” – subtly captures the inherently cyclical nature of imperial history, a periodicity at odds with epistemological constructs of eternal Western development as well as the problematic colonial maxim “The sun will never set on the British empire” . As such, Conrad extends little of the august sentiment for imperialism exuded by much of his late-1800’s Europe, a culture convinced of its central role in cultivating a similarly civilised light in the distant ‘Dark Continent’. Instead the author implicates the ‘problem’ of its own colonised history and the darkness and ephemerality that this entails.

Rhetoric as Deception

In Kurtz’s writing in passage two “vibrating with eloquence”, therefore, Conrad characterises this colonial rhetoric as its own pulsating, albeit problematic, entity, a resonating ‘voice’ for Marlow that represents the “unbounded power…of words”. These “seventeen pages of close writing” seem to breathe forth a form of mystical effervescence for Marlow, a “magic current of phrases” that sweeps him up in its moving composition. The ‘spell’ of sorts he seems to be put under here, speaks to the troubling quality for such flowering commentary on imperialism to enrapture, with an underlying note of enthrallment captured in the incantatory fricative of this “vibrancy” as it begins to resonate with and enchant Marlow. This report, an “exposition of a method” for the governing interactions between coloniser and colonised, epitomizes the vaulting rhetoric of the West, the “beautiful…writing” rife with benevolent proclamations of the virtues of the imperialist endeavour. Certainly, Marlow seems to echo – albeit at times sarcastically and resentfully - the colonialist discourse of Kurtz’s work, the notion of a redeeming “idea” of empire as something to “bow down before” in veneration. Given its ability, as Kurtz posits, to “exert a power for good”, Conrad thus depicts how the West consumed and later expounded on the beguiling rhetoric produced by the likes of Kurtz. These “burning noble words”, therefore, take on a damaging quality in their ability to promote such glorified idealisms of empire, providing, as is the case in passage one, a medium through which the Manichean binary of Western light and African darkness can be sustained. Kurtz’s words clearly become a captivating timbre for Marlow, with Conrad rendering his speech in the second passage into long, meandering constructions to reflect, seemingly ironically, an ineloquent attempt to communicate to report’s articulate quality. Kurtz is, after all, a product of his words for Marlow; whilst he may not be “prepared to affirm the fellow was exactly worth the life…lost in getting to him”, the ‘voice’ remains, offering means for justifying the “unselfish belief” in an idealised, reified version of the colonial institution. What this rationale is, however, remains fittingly unvoiced – “a power for good…etc., etc.”, “‘the might as of a deity’ and so on, and so on” – leaving no illusions for the reader as to Conrad’s critique of the hollowness of such supposedly ‘redeeming’ rhetoric. In doing so, the passage suggests the tenebrous reality of these imperialist disquisitions; how, in their capacity to “soar” in the mind of reader, they beguile and deceive as to the true horrors perpetrated by empire. The “International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs” for which Kurtz writes, epitomises this obfuscatory façade of civility and enlightenment, since its formal title simultaneously erects a pretence of decorum and distances itself from the dangerous ‘Other’ of the African wilderness. This company is a condemnatory allusion from Conrad to the likes of the ‘International African Association’ and the ‘Committee for the Study of the Upper Congo’, imperial institutions which worked under a mask of philanthropic curiosity and the corrective measures of the Berlin Conference to perpetrate the slaughtering of innocent Congolese in their sordid pursuit of land. The imminent dangers of imperialist rhetoric are hence brought to the fore: the destructive nature of colonial hegemony was presented in this late-Victorian era, tragically, as morally redeemable, with the harrowing reality hidden behind an opaque veneer of hallowed Western progression.

Existential and Moral Quandaries

So, when the entrancing “voice was gone” for Marlow in passage three, Conrad works to communicate the enervating psychological trauma of a daunting new reality without the reassurance of Western rhetoric. The perfunctory nature of this admission, in its sympathetically despondent tone, stands in stark contrast to the flowering panegyric Marlow proffered regarding Kurtz’s writing in the second passage. There is a distinct element of tragic fatality, as he bluntly blows “the candle out”, leaving the body behind in the dark room and thus figuratively extinguishing the life of this “remarkable man” and the “magnificent eloquence” that was alleged to be within. Marlow here is understandably confronted by the sudden and distinctly unglamorous pronouncement of Kurtz’s passing – “Mistah Kurtz – he dead”, and his voice as such rings of an antagonised disdain for the institution of empire, with the sibilance of “serene…smile of his sealing the unexpressed depths of his meanness” insidiously draping the manager in a cloak of malevolence. In taking his place “opposite the manager”, therefore, Marlow passively positions himself in antagonistic ideological opposition to this figure of European colonialism and all of the nefarious and avaricious principles which the man represents. He had, of course, already experienced well before this point the vile acts committed in the name of cultural enlightenment, yet there was still a latent sense of “getting to” Kurtz by journeying up river as offering the climactic vindication that could “save” Marlow’s idea of the enterprise from the sordid reality of these horrors. For Marlow, the tragic and abrupt disappearance of this possibility brings closer the impending and ominous isolation created by his trauma; though “there was a lamp” in the room with him, the Congolese wilderness outside seems to suffocate this artificial light in its “beastly, beastly” darkness, with the repetition here affirming the abominable outlook that pervades a nihilistic aspect shaped by comprehensive contempt for the failures of Western colonialism. The polluted “impalpable greyness” he endures, in its neither being only white or black, augments the conflicting tensions that characterise his confusing experience – he has “peeped over the edge” and comprehended the darkness below, yet draws back his “hesitating foot” in his unwillingness to leave behind altogether the ‘light’ of Western imperialism. Indeed, though the candle of Kurtz’s life can easily be snuffed out, the “brute force” and “aggravated murder” he has observed have cumulated into a “crop of unextinguishable regrets”, an awareness of “some knowledge of yourself”, with the second person construction allowing Conrad to ask his own 19th century readership to confront the uncivilized and contemptible darkness of empire that they, too, have observed, facilitated or denied. That the report in passage two only appears as “ominous” in the “light of later information”, the novella presents what critic Ian Watt described in his 1972 lecture as ‘delayed decoding’, where it seems Marlow comes to terms with what he has seen only after the fact, a reaction that “comes too late”, thus allowing the reader to share in his emerging, thoroughly ‘modern’ awareness of the confronting truths regarding the vacuous amorality of the imperialist enterprise. In essence, then, Marlow’s recounting in these passages, having occurred after the death of Kurtz and the subsequent dismantling of a redeeming entity to “offer a sacrifice to” in grotesque worship, comes to represent the confronting shift of Western thought that will, or needs to, occur in Conrad’s eyes, as his late-Victorian society begins to move away from its infatuation with and subsequent reliance on the glorified rhetoric of European colonialism and the rapacious hegemony it justifies.

A New Form of Belief

By still repeatedly upholding Kurtz as “a remarkable man”, however, Marlow’s self-reassuring insistence on maintaining this idolatry figure is suggestive more universally of a human desire and search for meaning. His forlornness and moral uncertainty comes to the reader across the passages in his euphemistic and opaque ruminations on empire throughout his journey – “an unselfish belief in the idea”, “the notion of an exotic Immensity”, “the expression of some sort of belief” – as each rendition becomes increasingly abstruse and confused in its vague generalisations. There is an underlying sense, for the reader, that, in Marlow’s unsettled and melancholic “vision of greyness”, his imprecise and distorted language allows him to paradoxically believe that he can “understand better the meaning of [Kurtz’s] stare”. His increasingly epiphanic speech reflects this pursuit of cognisance, as he first forcefully, if not somewhat desperately, rejects his despondent and “careless contempt for the evanescence of all things” – “No!” – before naively asserting that “Perhaps!” he can come to “why” he feels such a connection to Kurtz’s voice. Of course, his otherwise indecipherable transition from his nihilistic state of “tepid scepticism” to the significance of Kurtz’s experience is left merely as “That”, as though it were somehow better for Marlow to be able to conclude something, rather than be left in his former state of uncertainty. In Marlow’s lamentably searching tone, Conrad makes clear a deep-seated human need for a ‘rational’ light to make transparent the muddy waters of epistemological doubt and moral ambiguity, particularly in times of such ideological uncertainty and transition. The author leaves Kurtz’s rasping final cry of “the Horror!” as purposefully inconclusive in regards to what so gripped or disgusted him in this dying moment, whether it be the moral bankruptcy of empire, the harrowing African jungle or perhaps a vision of man’s intrinsic potential for corruptive evil. So ingrained is Marlow’s need to draw meaning from Kurtz’s life as the supposed rationalising agent of an otherwise sordid colonial entity, that he can definitively claim that it “was an affirmation, a moral victory”. This determinism is ironically undercut in the sense that Marlow thinks he can know what was meant, yet as a result he imbues the cry with his own interpretation and thus moves further away from an objective ‘truth’, whatever that may have been. In this way, Conrad articulates to a Western readership - still firmly entrenched in the ‘eternal’ structures of empire - that, contrary to a traditional notion of an objective truth or universal meaning, human language and experience is inherently subjective and oft-impenetrable, often unable to be made comfortably transparent. The rhetorical writings of Europeans like Kurtz providing “future guidance” for Marlow and other expeditioners thus become vessels for removing these colonisers from the confronting and traumatic destruction of imperialism, as they satisfy man’s internal journey to find reassuring moral validity for their endeavours. In doing so, these passages attest to Conrad’s pre-modern narrative structure that sought to rend the comforting ontological systems of imperialism and thus position a Blackwood’s readership to challenge their own culpability and belief in the ‘redemptive’ morals of empire.

Heart of Darkness, Conrad, and Cultural Myopia

On The Pall of Western Rhetoric and Colonialism